Vokzal (2016)

16mm color film, audio

58 minutes

Installation variable

Vokzal is a looping, 16mm film shot by Leigh Ledare in 2016. Running nearly 60-minutes, Vokzal uses the sprawling public space connecting three Moscow train stations as a rubric for mapping latent social dynamics. Inside the station complex—itself a threshold where the country’s farthest corners converge with its economic center—symptoms of structural violence are passed over by the banal yet complicated choreography of transit. The film captures interactions between numerous subjects passing through, working in, loitering around or policing this public zone—inside of which the cohabitation of transgression, authority and quotidian routine mirrors the fractures of social hierarchy. Just as competing ideas of order play out, instances of individual behavior reveal clear signs of social breakdown. Laying bare a collective predicament, Vokzal ultimately serves not as a portrait of Russian society alone, but that of a society which—caught within a vicious circle of splitting and projection—is stranded between forms of dependency, fight-or-flight response, pronounced individualism, or non-differentiation.

The slow-motion visuals of the film are synced with Drew Brown remix of the Dusseldorf band Neu!’s 1973 track ‘ Super 16’. Neu!’s original manipulated analog tape recording—with its slowed-down, swampy cadence and repetitive metronomic structure—accentuates a palpable feeling of anxiety. Its pulse drives the dérive and drift of perspectives—both of the film’s subjects, and Ledare’s own camera—as they circulate through the confines of the station.

Vokzal, the Russian word for station, derives its etymology from Vauxhall, the outlying destination of Russia’s first railway line built in 1838 between St. Petersburg and the Imperial palace in Pavlovsk. At this site, an elegant station was erected, the interface between a dancehall and lavish pleasure garden—for which the word vokzal also became synonymous. Modelled after London’s Vauxhall Gardens, this heterotopian space revealed the increasingly westward looking cultural aspirations of Russian Imperialism. In German, vokzal transliterates as “hall for common people,” forecasting how—like the train itself—its exclusivity would eventually be undermined by its utility for the proletariat. In turn, while constituting one of the primary symbols of Soviet cultural progress, Moscow’s central terminal train hub would, under Russia’s adoption of capitalism, give way to the station’s contemporary condition as “junkspace”. Rem Koolhaus writes: “Modernization had a rational program: to share the blessings of science, universally. Junkspace is its apotheosis, or meltdown... Although its individual parts are the outcome of brilliant inventions, lucidly planned by human intelligence, boosted by infinite computation, their sum spells the end of Enlightenment, its resurrection as farce, a low-grade purgatory...” The itinerant definitions and implications of this title—both geographically and logically—anticipa te the shifting positions and contingent meaning in relation to Vokzal ’s subjects, sites and viewers.

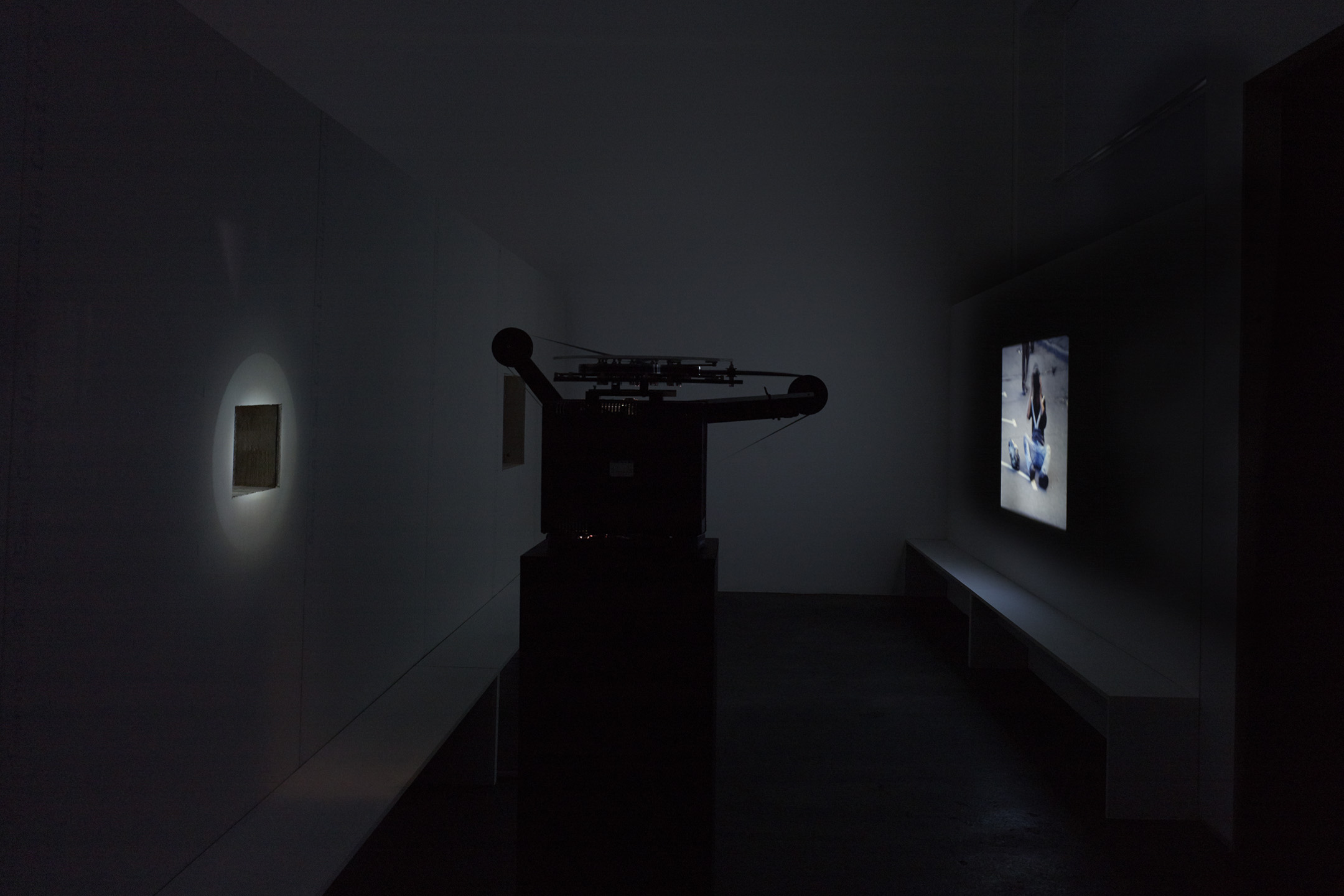

Vokzal was first presented at Office Baroque, a gallery overlooking ‘Place du Jardin aux Fleur’, a now neglected public square in central Brussels that—like the Russian station—centers around a fountain. Ledare blacked out the gallery’s windows, creating a cinematic space inside the gallery and, outside, an opaque mirror that reflected the square back to itself. Resonating with the strategies of artists such as Michael Asher, the act of displacement and recontextualization enacted by Vokzal’ s installation staged what might be described as a reflexive ethnography—rather than simply studying the other, these intersubjective encounters mirror back our own alterity. The site specific installation further emphasized this reflexivity through its architectural construction. The gallery’s main room—transformed into a black box—was bisected lengthwise by a freestanding 38’ long x 26” wide corridor. This architectural intervention functioned as a psychological passageway and barrier, splitting the space into two interconnected waitin g rooms. The complete 60-minute film was divided into three 20-minute, looped projections. Three projectors, positioned on plinths in either waiting room, cast their respective segments of the film from one room—through incisions intersecting the corridor’s walls—to the far wall of the room opposite. These punctures created a second intersecting, non-physical structure. In turn, the viewer’s body—passing through the blind spot of the corridor—created an eclipse, casting an interruption between the projector and the field of subjects initially captured by the camera. Thereby mapped into the film of the station, the presence of the viewer’s shadow materializes another set of thresholds—between subject/object, site/non-site, and seen/unseen.

The interplay between physical and non-physical structures within Vokzal —between the world of the station, and the shared structural, social, psychological and linguistic systems brought together by its (re)staging—function as a lacunae, a language gap around which collective antagonisms persist, further laying bare our predicament.

link to film

password: Vokzal

documentation of installation

password: vokzal install

16mm color film, audio

58 minutes

Installation variable

Vokzal is a looping, 16mm film shot by Leigh Ledare in 2016. Running nearly 60-minutes, Vokzal uses the sprawling public space connecting three Moscow train stations as a rubric for mapping latent social dynamics. Inside the station complex—itself a threshold where the country’s farthest corners converge with its economic center—symptoms of structural violence are passed over by the banal yet complicated choreography of transit. The film captures interactions between numerous subjects passing through, working in, loitering around or policing this public zone—inside of which the cohabitation of transgression, authority and quotidian routine mirrors the fractures of social hierarchy. Just as competing ideas of order play out, instances of individual behavior reveal clear signs of social breakdown. Laying bare a collective predicament, Vokzal ultimately serves not as a portrait of Russian society alone, but that of a society which—caught within a vicious circle of splitting and projection—is stranded between forms of dependency, fight-or-flight response, pronounced individualism, or non-differentiation.

The slow-motion visuals of the film are synced with Drew Brown remix of the Dusseldorf band Neu!’s 1973 track ‘ Super 16’. Neu!’s original manipulated analog tape recording—with its slowed-down, swampy cadence and repetitive metronomic structure—accentuates a palpable feeling of anxiety. Its pulse drives the dérive and drift of perspectives—both of the film’s subjects, and Ledare’s own camera—as they circulate through the confines of the station.

Vokzal, the Russian word for station, derives its etymology from Vauxhall, the outlying destination of Russia’s first railway line built in 1838 between St. Petersburg and the Imperial palace in Pavlovsk. At this site, an elegant station was erected, the interface between a dancehall and lavish pleasure garden—for which the word vokzal also became synonymous. Modelled after London’s Vauxhall Gardens, this heterotopian space revealed the increasingly westward looking cultural aspirations of Russian Imperialism. In German, vokzal transliterates as “hall for common people,” forecasting how—like the train itself—its exclusivity would eventually be undermined by its utility for the proletariat. In turn, while constituting one of the primary symbols of Soviet cultural progress, Moscow’s central terminal train hub would, under Russia’s adoption of capitalism, give way to the station’s contemporary condition as “junkspace”. Rem Koolhaus writes: “Modernization had a rational program: to share the blessings of science, universally. Junkspace is its apotheosis, or meltdown... Although its individual parts are the outcome of brilliant inventions, lucidly planned by human intelligence, boosted by infinite computation, their sum spells the end of Enlightenment, its resurrection as farce, a low-grade purgatory...” The itinerant definitions and implications of this title—both geographically and logically—anticipa te the shifting positions and contingent meaning in relation to Vokzal ’s subjects, sites and viewers.

Vokzal was first presented at Office Baroque, a gallery overlooking ‘Place du Jardin aux Fleur’, a now neglected public square in central Brussels that—like the Russian station—centers around a fountain. Ledare blacked out the gallery’s windows, creating a cinematic space inside the gallery and, outside, an opaque mirror that reflected the square back to itself. Resonating with the strategies of artists such as Michael Asher, the act of displacement and recontextualization enacted by Vokzal’ s installation staged what might be described as a reflexive ethnography—rather than simply studying the other, these intersubjective encounters mirror back our own alterity. The site specific installation further emphasized this reflexivity through its architectural construction. The gallery’s main room—transformed into a black box—was bisected lengthwise by a freestanding 38’ long x 26” wide corridor. This architectural intervention functioned as a psychological passageway and barrier, splitting the space into two interconnected waitin g rooms. The complete 60-minute film was divided into three 20-minute, looped projections. Three projectors, positioned on plinths in either waiting room, cast their respective segments of the film from one room—through incisions intersecting the corridor’s walls—to the far wall of the room opposite. These punctures created a second intersecting, non-physical structure. In turn, the viewer’s body—passing through the blind spot of the corridor—created an eclipse, casting an interruption between the projector and the field of subjects initially captured by the camera. Thereby mapped into the film of the station, the presence of the viewer’s shadow materializes another set of thresholds—between subject/object, site/non-site, and seen/unseen.

The interplay between physical and non-physical structures within Vokzal —between the world of the station, and the shared structural, social, psychological and linguistic systems brought together by its (re)staging—function as a lacunae, a language gap around which collective antagonisms persist, further laying bare our predicament.

link to film

password: Vokzal

documentation of installation

password: vokzal install